Point #5: Improve Constantly and Forever the System of Production and Service

“Kaizen means ongoing improvement involving everybody, without spending much money.” – Masaaki Imai

Where it came from

Post WWII, Japan’s economy and its infrastructure were in ruin; how were they supposed to re-build their economy with very limited resources? With available cash being a huge constraint, Japanese companies had to find ways to get cash back to their businesses in the shortest time so they could keep afloat. This forced them to get creative and to put focus on making their processes more efficient by reducing move, queue and process times to lower throughput. This, with the focus on delivering higher quality, meant they could delivery a higher variety of products, in small batch numbers at low cost.

Kaizen became a central part of Japanese business culture and this philosophy emphasises that everyone be involved in making small, incremental improvements to the process.

Some of the key concepts include having respect for people, managers who work on improving the system, the elimination of waste, variation and defects and the focus on small incremental gains.

This philosophy is not new… it has been around for over 80 years; so why aren’t we all working in businesses that are run like this?

How did we end up here?

Post WWII America wasn’t as financially constrained as Japan, and so they focussed on economies of scale to lower the manufacturing cost per unit rather than on economies of flow(1).

Henry Ford was able to bring cars to the masses by cheaply producing a single model of car. This brought huge economies of scale as he was able to produce more and in a shorter time than anyone else and thus was able to make a profit on a lower sale price. The only issue with Ford’s model is that he wasn’t able to offer the customer variation “You can have any colour you want as long as it’s black”.

As other businesses caught on to Ford’s model, they too employed economies of scale to reduce their cost per unit. However when the customers wanted more variation, they weren’t able to keep their cost per unit as low due to time spent changing over and dealing with more variety in their processes. To tackle this problem they simply kept the economies of scale, making different models in larger batches (whether or not they had been sold) and then changing over to make the next variation in a large batch.

As customers are demanding more and more variation, the old model is quickly becoming out-dated and many companies are ill equipped to deal with it because of a lack of understanding and implementation of lean.

Why people hate change

Wrong mindset and approach by management

“People hate change…”

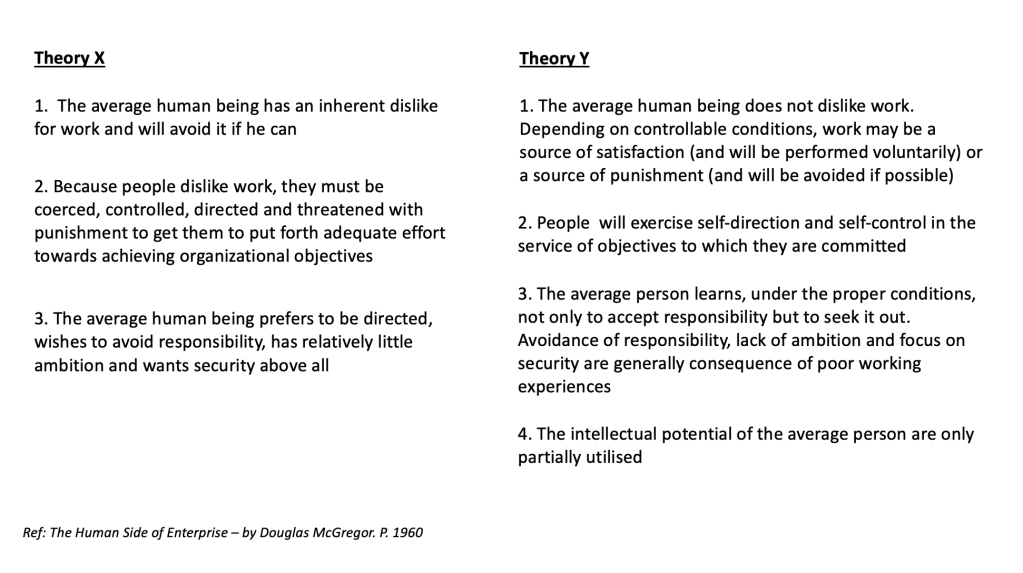

I hear this all of the time… and I have found it to be true only when change is forced upon the people by management who make decisions far removed from where the work is actually done. In these cases, the benefits for the business are sometimes (but not always) clear to the people and often they actually make the work harder and not easier for the workforce.

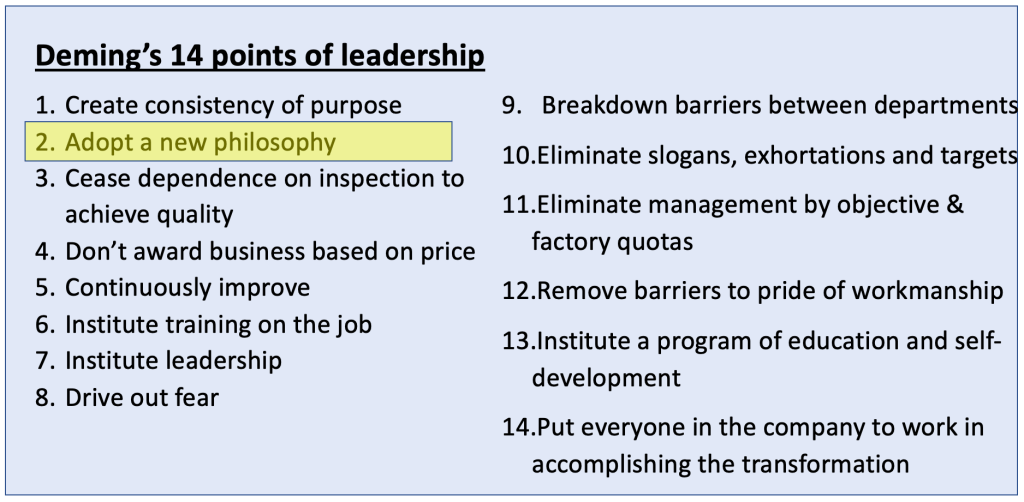

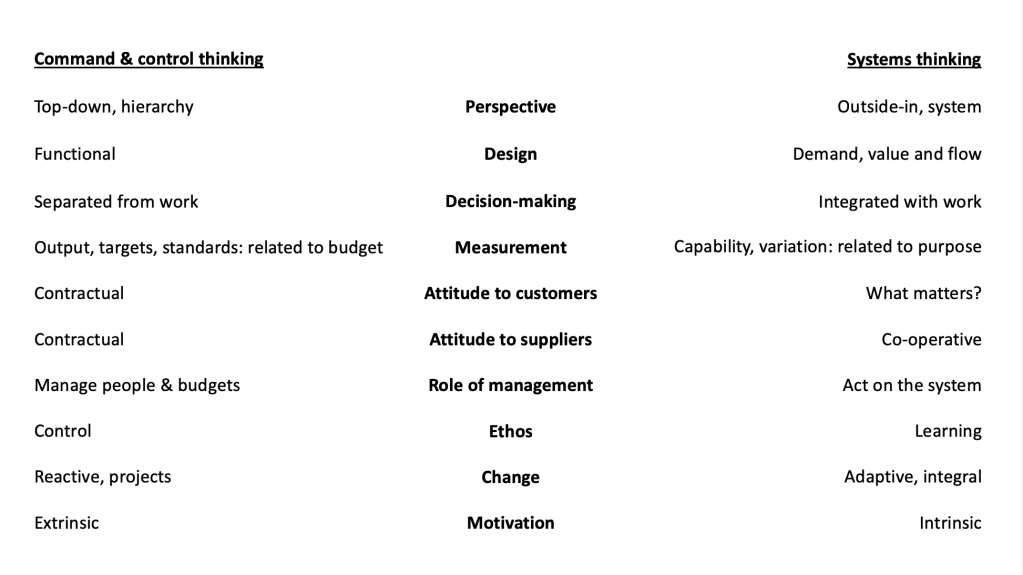

Working in this way is not systems thinking (see Point #2) and is not what continuous improvement is about.

If you approach change in the right way and with the right mindset, then people will ask you for change rather than resisting it.

Peter Senge put it so simply by saying that “People don’t resist change. They resist being changed!”

So rather than force change upon someone, instead ask them what changes would make their jobs easier and more efficient and then do those things. Helping the people by making their jobs less frustrating will make them more receptive to changes that you suggest in the future because you will have gained their trust and appreciation. A happier workforce will be safer, produce higher quality and be more efficient; eliminate day to day frustrations and constraints on them doing a good job and they will thank you for it.

Tool heads and consultants

Many people believe that continuous improvement or lean is just a set of tools that you can buy off the shelf and put in to your process. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Continuous improvement is first and foremost a mindset and work must be done to change your mindset from the old school thinking to systems thinking (see Point #2 for more detail on this)

As the Toyota Production System gained popularity in the West in the 1980’s it was pretty much inevitable that lean manufacturing “tools” would emerge as a way to emulate the processes used by the Japanese. The principle behind the creation of these tools was that you could get the desired level of improvement by blindly implementing the “lean tools” in your business… sounds simple and too good to be true right? Well that’s because it is!

Tools like 5S, TPM, Takt time, Value Stream Mapping etc. are often implemented irrespective of the true need for them which go against the core principles of CI.

These tools are at best an aid and can in some cases bring small benefits but they don’t tend to actually change the system at all. What we learn from both Deming and Seddon is that you must change the system for things to truly improve. Any benefit that you do get from the blind implementation of tools pale in comparison to the results you get from teaching others perspective and how to think about problems that need to be solved.

I’ve seen many “lean consultants” brought in to try and “fix” businesses and they all do as they have been taught and apply the tools in a blanket and unthinking way, rather than leading with the right questions.

Here is a question to ask yourself: What is the primary objective of a “lean consultant”? Is it to improve your business? Or is it primarily to sell you more of their time? I’ve seen consultants tell their customers that they won’t see any improvement from implementing their prescribed activities for over a year… a year?! So you have to pay for their time and pour resources in to something for over 12 months before you see any benefit? How is that lean?

At one of the plants I’ve worked at, we took things back to basics and took a systems approach to continuous improvement (see Freedom From Command and Control by John Seddon) rather than employing consultants to implement tools. In 4 months and with a spend of less than £10,000, we improved our overall factory output by 5%. That’s 5% extra product made with the same people and the same machinery, working the same shift pattern as before.

Consultants can cost over £3K per day for their time (and then you still have to pay their expenses)…. so for the cost of less than 3 days of consultant time, we saw a huge improvement in our output AND we did it in 1/3 the time.

What we created in the process was a continuous improvement framework that we continuously use and refine and that we have moved to other areas of the factory as they became the bottleneck process.

The small improvements we made were done at minimal or no cost. We did this by surfacing and eliminating the failures in the bottleneck process; and we did this by involving every person who worked in that area.

What can we do about it?

Know where you are going

If you haven’t already, go back to read Deming’s point #1 on creating consistency of purpose; if you don’t know where you are going as a business, how can you decide where to start making improvements?

Educate yourself in the principles of lean

Here are some must-reads if you want to gain an understanding of what true lean is:

-Freedom from Command & Control – by John Seddon

-Out of the Crisis – by W.Edwards Deming

-Beyond Command and Control – by John Seddon

-The Goal – by Eli Goldratt

-Better thinking, better results – by Bob Emiliani

-Real Lean – by Bob Emiliani

Mindset is more important than tools and techniques and the above books should start to shape your mindset

Instigate respect for people:

Respect for people is a key aspect of the continuous improvement process. Respect for people ultimately means creating a safe and collaborative environment where everyone is valued, empowered and supported to reach their full potential. In “old school” organisations, the “us and them” mindset is rife, people on the front line aren’t listened to or involved in decisions that are made by management. It is critical to create a culture where everyone works across functions and levels of seniority to improve the system.

Whether you are employed in a business that makes cardboard boxes or make cat food, you are all there to supply the product or service, safely, at the right quality & cost for a price that the customer is willing to pay. And irrespective of your position within the organisation, you are all there to play your part in delivering on that mission.

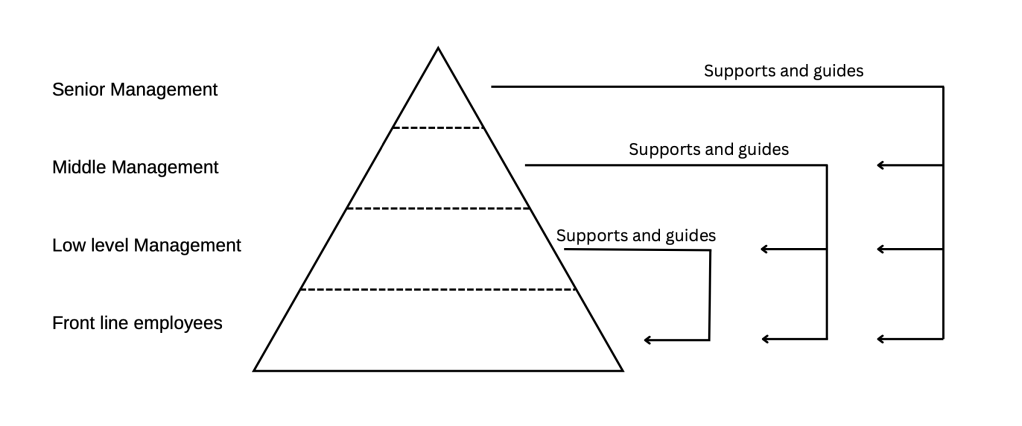

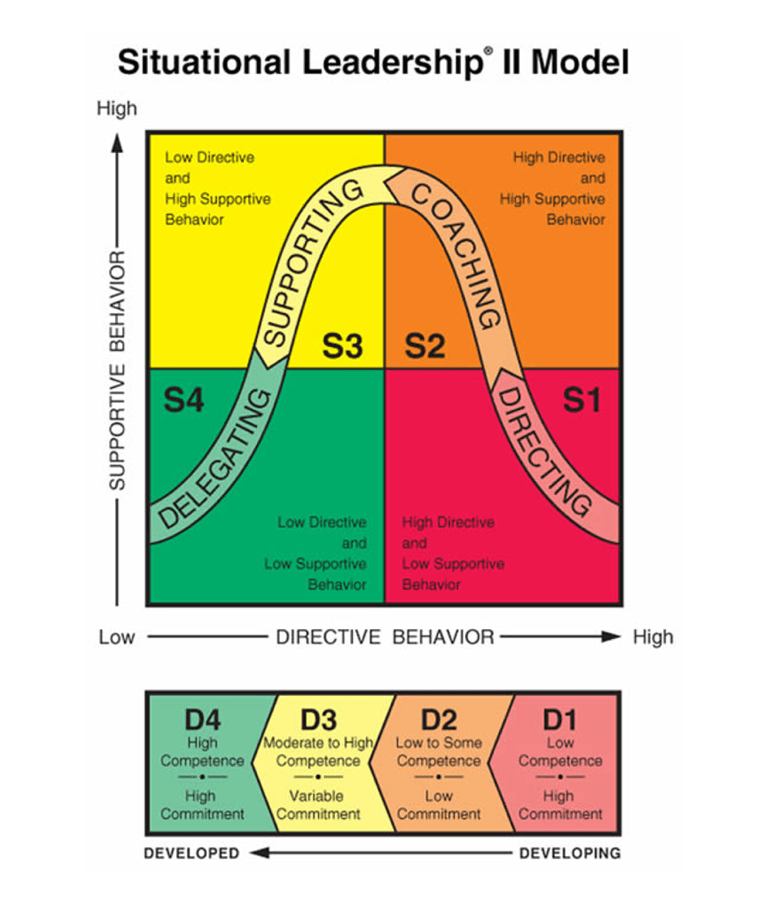

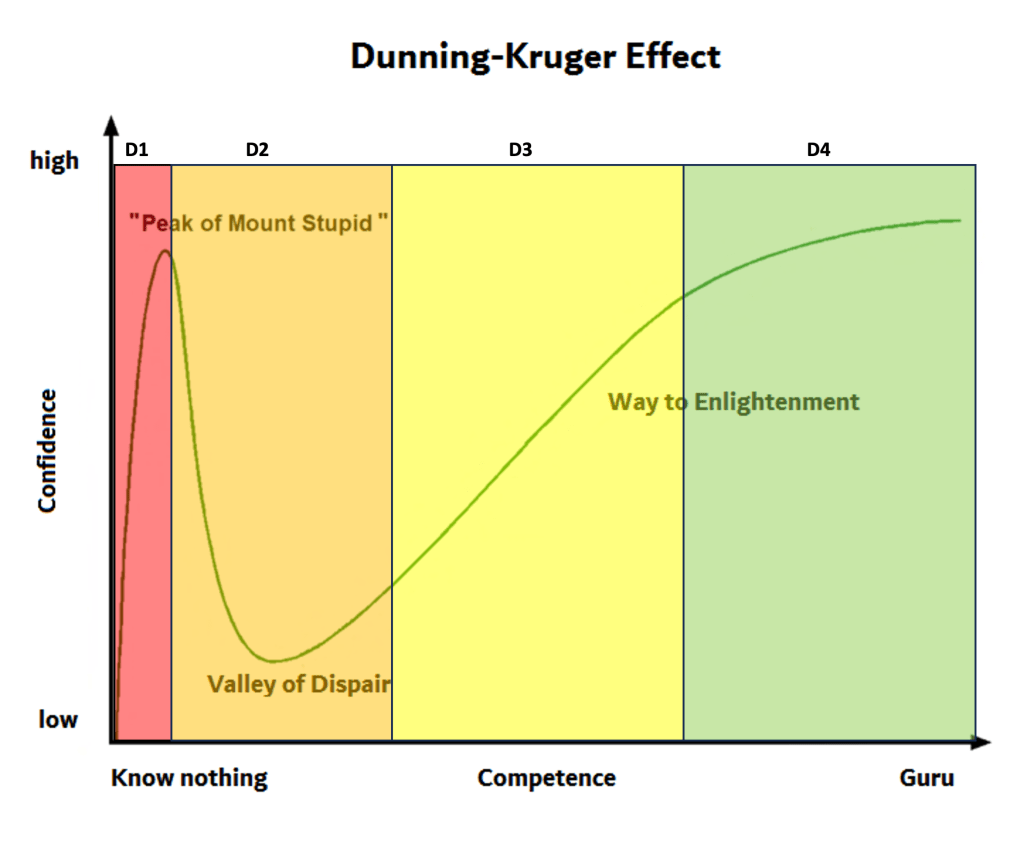

What this also means is that you need to trust the people in middle management and supervisory positions to make decisions. This means accepting that they may make mistakes from time to time and it’s your job to coach and guide them. Every time they make a decision, they will likely make an even better one next time.

Think about how you can:

- Devolve more of the day to day decisions to people at lower levels within the organisation

- What training and support would they need to do this effectively?

- Give the people on the front line a voice to raise problems that they face each day which takes away pride of workmanship and makes their job harder?

- How can you solve their problems as if they were your problems?

Where does data fit in?

Fomula 1 is a great way to illustrate progress that has been made through continuous improvement; 50 years ago, the pit stops alone were over a minute and now are under 3 seconds.

What data do you think the F1 teams had before they started to look at pit stops? Probably just the knowledge that the pit stops were a necessary process in the race, and reducing the time it takes to perform the process, means less time spent with the car stood still.

Back in the 70’s, the technology simply wasn’t available to get the thousands of data points needed to bring the pit stop to it’s current levels, but much progress was made by observing the process with stop watches and continuously finding and eliminating the slowest process.

You’d have teams of people with stop watches and clip boards watching the pit crew perform their process repeatedly, all the while making notes on what they saw. Once they’d done this several times, they’d likely have shared their observations with the crew and asked the crew themselves about their own experiences and what they found hard about the process they were performing.

Most businesses aren’t all the way back in the 70’s when it comes to the data but they aren’t advanced in their lean journey to be able to use the data they have in a meaningful way. A lot of businesses would benefit from the pit stop approach described above to make improvements in their processes.

This approach to problem-solving and continuous improvement has respect for people at its core. The opinion and experience of the pit crew is important and is a key source of data to help the improvement efforts.

- Do you know what your slowest process is?

- What observations have you made of that process which might be slowing it down or making it harder for the people to do their work?

- What do the people think could be done to make their jobs easier?

Remember that you won’t necessarily be able to quantify the value of each improvement that you make. As long as you are taking actions by involving the people and that is based on the work that is done, then you will likely be heading in the right direction. If you make someone’s job easier, then you will likely be more efficient than you were and in many cases, you don’t need complex data systems, just spend time on the shop floor, making observations and speaking to your people.

In most cases you don’t even need any sort of sophisticated problem-solving tools beyond asking “Why” until you get to a root cause. Don’t over-complicate things and you will make it easier to involve more people in improvement.

Walk your process multiple times a week

Going to the place where the work is done and speaking to the people on the front line is critical to understanding what work is actually done and the problems that the team face in doing it.

Walking the process and speaking to the people builds trust and allows you to gain perspective and see first hand, all of the obstacles that hinder a great days work. Armed with this new understanding of the process and a better relationship with the people, you will be better able to make changes that help rather than hinder your team.

Level everyone up:

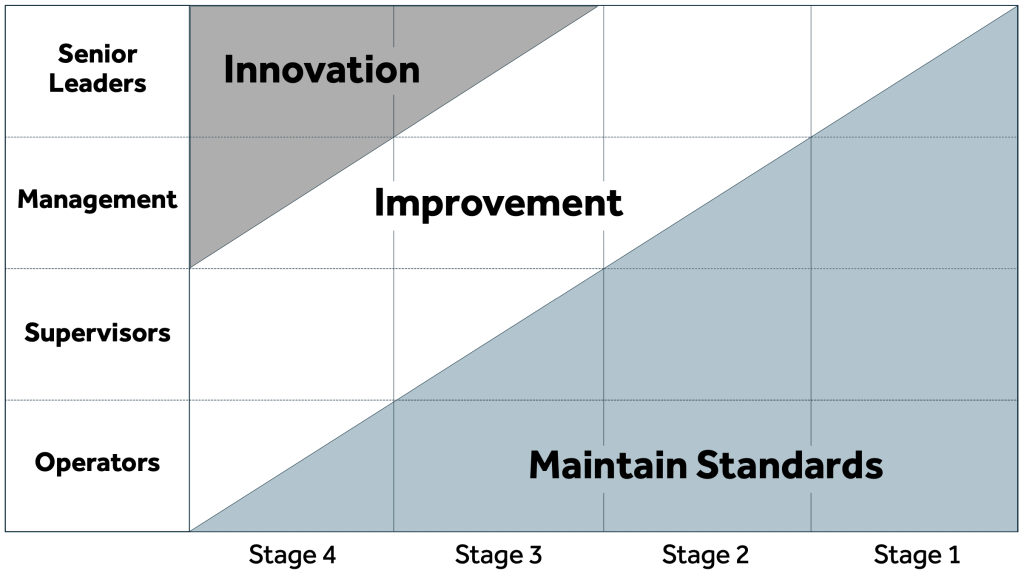

The Kaizen (or improvement flag) like the one displayed below, shows the primary focus of employees at each level of the organisation depending on how mature you are in your continuous improvement process.

Stage 1 means that you are likely to be highly reactive, most people in the organisation are focussed on fire-fighting just to maintain the standards and only those in senior leadership have any time to make improvements.

In stage 2, your senior leaders are mostly focussed on improvement, the middle managers are involved in some level of improvement on the site, and everyone else just works to maintain the standards

In stage 3, your senior leaders work on improvement and innovation, your middle managers work on improvement, your supervisors are now involved in improvement and the workforce still mostly maintain the standards.

In stage 4, the senior leaders have the time to focus almost solely on innovation, your middle managers do innovation & improvement, your supervisors do improvement and your workforce take part in improvement and maintaining the standards.

How do you move up in maturity?

The process of levelling up the business is the same as levelling up the people and I’d say it’s all about time & focus. If you are constantly firefighting because your machines keep breaking down and you can’t maintain your quality, then what do you think you need to do to give yourself and your people more time to focus on levelling up?

You need to put focus on improving things or fixing them once and for all rather than simply fighting to get things back to how they were. This will free up more and more time to focus on ever more improvement activities leading to a positive loop.

You will need to trust your people and allow them to make decisions in the knowledge they will make mistakes from time to time but that they will also learn and make better decisions next time. You are there to guide them should they need it and you’ll be there to coach them and go easy on them when they make a mistake (which they invariably will).

Start by focussing your attention on the biggest issues in your bottleneck area, not just the one off spikes like the big breakdowns (special cause variation) but the smaller things that affect the day to day (common cause variation) and accept you won’t be able to fix everything all at once.

When you are faced with a problem think:

- What are the symptoms of this problem?

- What is the root cause of the problem? (use 5 whys)

- What is the short term fix? (to get us back up and running)

- How can we dissolve the issue so it never comes back?

It may seem painful at the start because you will be dealing with firefighting and with some level of improvement but before long, you can

A note on variation:

There are two types of issues that will cause variation in your system, common cause (the little things that happen frequently and cause minor stops) and special cause (the big, one off events that cause big stops).

People tend to focus a lot of their efforts on the special cause events because alone, they are painful and cause a lot of disruption to your process. However, the bigger loss comes from the common cause issues.

Focus on flow:

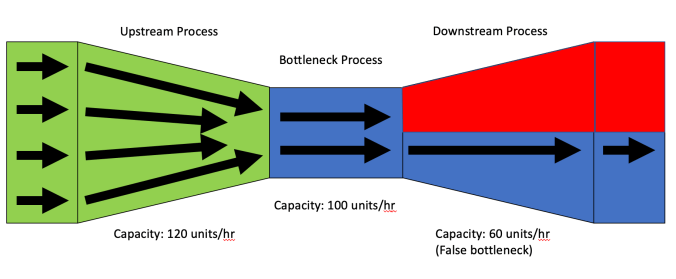

To achieve flow within a system means that product moves through uninterrupted with minimal move, queue and process time. The slowest process within a system is called the bottleneck. To achieve flow, you must focus on improving the queue, move and process time of the bottleneck.

To improve a process that is upstream of the bottleneck will just increase queue times and to improve the process downstream will just increase wait times for product as the bottleneck will still restrict flow within the system.

You don’t always need numerical data to find the bottleneck within your system; the bottleneck process will have WIP piled up in front of it and the processes downstream will be waiting for work. Which process / department has the most backlog in their work that is holding up the entire system?

I’ve seen places where they got artificial flow by restricting output of the process upstream of the bottleneck. In this factory, the true bottleneck was the finished goods process and the manufacturing process upstream would continuously experience down time as the product buffer had backed up all the way to the outfield of the machines (build up of WIP). Rather than focus efforts on improving the bottleneck process to achieve flow, they restricted the output of the manufacturing process (by turning off machines). This made it look like they had flow but ultimately the output of the factory remained the same.

Find the process that is restricting flow within your system and make that the focus point for your improvement activities.

Bringing it all together:

Below is an example of how we’ve brought all of the above together, to kickstart our improvement journey.

You’ll need to start by finding the bottleneck within your system (If you haven’t already, read article #2 to learn more about how to find it). Once you’ve established where this is, pick a small team to focus on improvement in that area (as a minimum, the person who is responsible for that process and a person who is responsible for maintaining it).

Next you need to decide upon what data you are going to record so you can track your improvement process. Article #2 has some useful information on data and process KPIs.

Next, you need to understand what all of the failures are within the process so you can prioritise which to tackle first. We’ve done this using post-it notes and some brown paper (it’s crude but having something you can visualise makes the whole process easier).

This is what each section does:

- Data sheet to show results and targets for your process (updated monthly at a minimum)

- The breakdown of your process in to it’s constituent steps

- The process, queue and movement time of product through your process

- The list of all of the issues at each part of your process – filled in on post-it notes by 100% of those who do the work in that process

- The action tracker with your live top 5 projects (identified and prioritised by your team)

- Start dates of that project (you can’t know for certain when something will be fixed so you put on the start date to help hold you accountable to doing it as quickly as possible)

- The projects you’ve completed and the next highest priority projects to work on

The idea is that you keep this in a place where anyone can see it and where your team can add to it. The complexity of the issues you need to resolve will dictate how often you meet with your improvement team to update the actions. When I’ve wanted to spend time coaching the process owner on how to use the board, I meet them every day for 30 mins; as they get more comfortable with the process and with taking action, you can move this to 15 mins per week. The updates need to be short and snappy and must involve every person who has an action on the board.

It is the role of the improvement person to coach the process and that person should take minimal or no actions from the board.

By doing this, you are involving and developing your process owner and will involve 100% of the people who work in that process. This way, everyone has a voice and you are levelling up your process owner to focus on improvement activities rather than the day to day firefighting.

Now that you have this in place, you need to keep your finger on the pulse and your ear to the ground; you must walk the process several times a week so you can give and get feedback from your team as to how improvement efforts are working (or not working) for them. This is their opportunity to hold you, the leader to account on what you said you’d do to help them (and you should tell them that this is the reason for walking the process – and you’d better mean it!)

A final note on “Lean tools”

You can use the “lean tools” to help you make improvements but I have found that is just over-complicates things. Rather than spend time trying to understand how to “deploy” a tool by the book, learn about what the tool is trying to achieve and the reason that the tool exists. Then you will understand a concept that you can use much more efficiently and effectively than the tool.

For example, 5s is one of the go-to tools that people talk about when they think lean / continuous improvement; and nearly everyone gets it wrong! People think that it’s a workplace organisational tool but that almost couldn’t be further from the truth. 5s just means having the right tool in the right place that is ready for use when needed.

If you need to use a specific spanner to make adjustments and you use it multiple times per hour, then it needs to be placed near where it is to be used. As the frequency of use decreases, it can be placed elsewhere, further away from the point of use; otherwise it will clutter your workspace and will take up space for more commonly used things. Deciding on what needs to be closer or further away from the process is simple and can be done very quickly; sometimes in a matter of days.

If you were to take the “lean tool” approach to implementing or “rolling out” 5s, you’d spend a week red tagging, a month with a pile of things in your area, then you’d get rid of all the stuff you haven’t used and would invariably end up throwing out something that you in fact did need. Using the concept of right tool in the right place is way more effective and easier to teach to others than strictly adhering to the 5s tool process and you get better and faster results.

I don’t strictly deploy any tools, I just ask what we can do to resolve and then dissolve the problems and I ask the team what they think would do that. I’d say that 90% of the time, the team who do the work have the answers (or get very close to them).

References:

(1) – Beyond Command and Control – Second Edition, by John Seddon Published 2003